January 2026

The Sky Tonight - January 2026

January continues the season of Birak, meaning the hot weather is here to stay. The silver lining is that the night skies are …

ExploreScitech will be closed 25th and 26th of December

Scitech will be closed 25th and 26th of December

Scitech will be closed 25th and 26th of December

Scitech will be closed 25th and 26th of December

As we enter the ‘second summer’ of Bunuru, the hot, dry weather continues with its correspondingly relatively cloud free nights.

The Southern Cross is making a slightly more impressive appearance in the southeast in the mid evenings. December and January are lousy times to view this constellation because it is so low in the southern sky its light gets heavily attenuated by the atmosphere, so it is nice to see it getting a bit higher up into better conditions. The same can be said for the pointers Alpha and Beta Centauri which guide the way to the Cross and are also increasingly easier to view as the month goes on.

Image: The Southern Cross and Pointers

This is handy if you’re planning on viewing the Alpha Centaurids meteor shower, which peaks around Feb 8. These meteors appear to emanate from Alpha Centauri, and in good conditions you might see half a dozen meteors per hour from this part of the sky.

Much higher up we can see the second brightest star in the night sky, Canopus, shining impressively throughout the night along with its parent constellation Carina. We can let our minds wander to the fictional planet of Arrakis from the Dune sci-fi franchise, which in the story’s canon is the third planet orbiting Canopus. It is not known whether Canopus has any real planets.

Image: The Southern Cross, Carina and Canopus

If you’re feeling up to the challenge, you may be able to catch a glimpse of Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF). This comet will be visible in the northwest sky around early to mid-February, though you will need binoculars or a telescope to see it. Observations of this comet will be made trickier by the moon being full in early February.

Jupiter is racing towards the western horizon and will be nearly gone by the end of the month so make sure you take this opportunity to take a last look at it before it disappears from the evening sky for a while. Later in the month it will be very close to Venus in the sky.

ISS sightings from Perth

The International Space Station passes overhead multiple times a day. Most of these passes are too faint to see but a couple of notable sightings are:

| Date, time | Appears | Max Height | Disappears | Magnitude | Duration |

| Feb 10, 5:17 AM | 10° above WSW | 59° | 10° above NNE | -3.7 | 6.5 min |

| Feb 10, 8:19 PM | 10° above NNW | 44° | 10° above SE | -3.5 | 6.5 min |

Table: Times and dates to spot the ISS from Perth

Source: Heavens above, Spot the Station

Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) makes its closest approach to Earth

February 1

The comet is close to Capella in the sky

February 6

Alpha Centaurids meteor shower peaks

February 8

Bright ISS sightings in morning and evening

February 10

The comet is close to Mars in the sky

February 11

Crescent moon above Venus in the west at sunset

February 22

Venus and Jupiter close in the western sky at sunset

February 28

Jupiter is visible in the northwest after sunset and is moving noticeably towards the horizon day by day. Meanwhile, Venus maintains a steady bright presence above the western horizon after sunset. The result of these two motions is that Jupiter gets visually closer to Venus as the month goes on, with the closest approach occurring on Mar 2. The crescent moon sits above Venus on Feb 22 so makes for great viewing of the three celestial bodies.

Image: Venus, Jupiter and the Moon above the western horizon on Feb 22

The quick motion of Mars across the sky has it currently located in the northern sky at sunset. It is not as bright as it was in December but still impossible to confuse with the nearby red stars Aldebaran and Betelgeuse, and even more difficult to overlook completely.

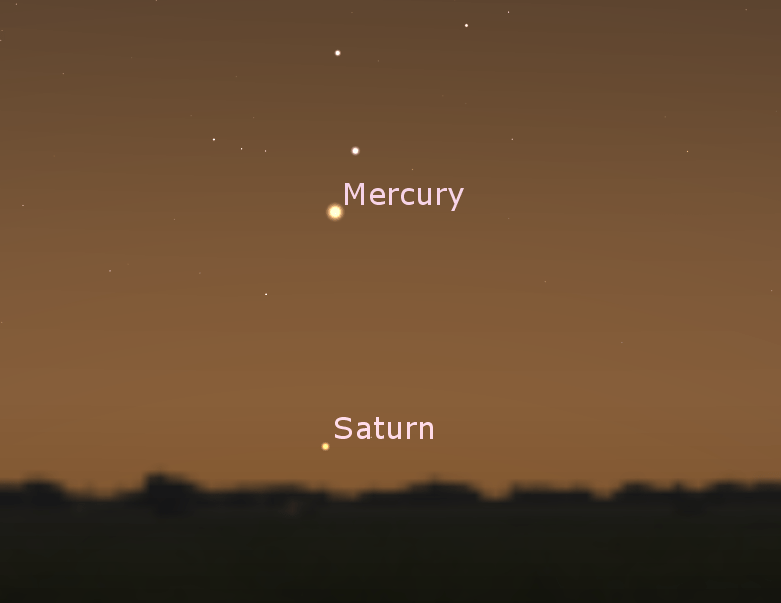

Saturn dips behind the sun this month so is gone from the evening skies. In the latter stages of the month it will appear in the east before sunrise, but it really isn’t worth getting up for.

Mercury is visible in the mornings in the eastern sky for the hour or so before sunrise. The planet actually reaches aphelion on Feb 15, putting it a distance of 69 816 000 km from the sun. With a perihelion of 46 000 000 km, only 65% as large, Mercury has the most eccentric orbit of the planets at a piquant e=0.21.

Image: Mercury and Saturn before sunrise in the east in the latter days of the month.

Interestingly, also on Feb 15, Venus and Neptune have an extremely close encounter in the western sky at sunset, but the extremely distant Neptune will be impossible to see without equipment, and extremely difficult with.

Auriga the Charioteer/Goat Herder

Auriga is a reasonably large constellation visible in the northern skies during summer months, located exactly opposite the galactic centre. Its brightest star Capella – the sixth brightest star in the night sky – takes its name from Latin for ‘Little Goat’. Combining Capella with nearby stars, some interpretations have taken Auriga to represent a herd of goats. Competing interpretations from various Greek stories have variations of a chariot, a charioteer or both.

In the second century, Ptolemy merged the stories and these days the constellation is usually represented as a charioteer holding reins in one hand and cradling goats in the other.

What appears to be a single bright star, Capella is revealed upon closer inspection to be 4 stars, consisting of a binary system of two yellow giant stars (Capella Aa and Capella Ab) similar to but much larger and heavier than the sun, orbited by another binary containing two red dwarf stars (Capella H and Capella L).

Capella Aa and Ab are in the process of leaving the main sequence, having fused all the hydrogen in their cores and are now evolving into the red giant stage, becoming larger and more luminous as they do so and together are currently about 160 times brighter than the sun.

Image: The pair of binaries making up Capella.

Credit: Giorgio Rizzarelli

Lying along the Milky Way, Auriga contains many fields of stars including the open clusters Messier 36, 37 and 38, each of them loosely bound groups of stars recently formed within the past few hundred million years.

During early February, Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) will pass through Auriga, roughly in the direction from Capella to Mars and will be visible through a decent telescope.

Comet C/2022 (E3) ZTF

By now you have probably seen news reports telling of the return of this comet to the inner solar system for the first time in 50 000 years. The comet passed perihelion on Jan 12, a distance of about 1.11AU from the sun and will make its closest approach to Earth on Feb 1, a distance of 0.28AU from us. The comet is hovering around magnitude 6 making it just barely visible to the naked eye as a green smudge in the sky.

Image: Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF)

That’s the theory anyway. While observers in the northern hemisphere have been able to observe it already, further south we have to wait a bit longer to get a good view of it in our sky. The relative motion of Earth and the comet will allow us to see it moving through Auriga in the early days of February, rising higher in our sky, roughly in the direction of a line drawn from Capella to Mars.

On Feb 6 the comet will be close to Capella in the sky and Feb 11 – 12 it will be close to Mars, so this is probably the best time to try and find it by using Mars as a reference.

Image: Location of the comet (blue, with dates) against the sky in February.

Credit: Bautsch

Having passed perihelion and on its way out of the solar system, the comet will start to fade in brightness so it is likely some observing equipment will be required.

Comets are notoriously unpredictable in just about every aspect. Commonly referred to as ‘dirty snowballs’ because of their mixed compositions of icy volatiles and rocky materials, they spend the majority of their time way out past Pluto in the Kuiper Belt and beyond. When they make a pass through the inner solar system, water and other volatile chemicals sublimate off the comet, clouding it in a brilliant coma, which is what causes it to get much brighter.

It is very difficult to predict how much material will vaporise off a comet, and hence how much its brightness will change as it passes by the sun. The vaporising material also has another effect – as it pushes off the surface of the comet it gives a little kick in the other direction, almost like a mini rocket engine. The combined effect of these little pushes from outgassing, as well as gravitational encounters with the planets limits the precision of calculations of the comet’s orbit for any reliable length of time into the future. Calculations of the comet’s orbit suggest that this is the last we will ever see of it. It has picked up too much speed from its foray into the inner solar system and seems to be on a course that will fling it out never to return.

Why such an awkward name C/2022 E3 (ZTF). As with many labelling systems, there’s method to the apparent madness.

C/ – Indicates that it is a comet that is non-periodic. Don’t ask when it’s coming back, it isn’t. Different letters before the / can indicate different information about the orbit.

2022 – The year of discovery.

E – Break each month in half and label them with letters, starting with A. So, A and B represent the first and second half of January respectively. ‘E’ represents the first half of March. Specifically, E3 tells us this was the third comet discovered in the first half of March.

(ZTF) – The Zwicky Transient Facility who discovered the comet.

So, C/2022 E3 (ZTF) is a non-periodic comet discovered by the Zwicky Transient Facility in the first half of March 2022 (March 2nd if you must know). Internationally, it was the third comet discovered during this period. Its non-periodicity means now is your last chance to see it before it never comes back.

Astronomers from the National Optical – Infrared Research Laboratory (NOIRLab) have released data from an enormous survey of the milky way. You really want to click this link to see a map of billions and billions of stars across the galaxy.

Image: Keep zooming and it just keeps resolving!

Credit: NOIRLab

The map was constructed as part of the Dark Energy Camera Plane Survey (DECaPS2). This map covers about 6.5% of the sky and contains approximately 3.3 billion stars. The survey was conducted at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chili, down in the southern hemisphere where the view of the Milky Way is best.

Of course, pictures like this contain three-dimensional data, and the importance of the DECaPS2 image is that many of the stars are at great distances, deep within the disk of the milky way galaxy. Studies like this provide information about the distribution of the stars, gas and dust within the Milky Way and allow a deeper understanding of the 3-dimensional structure of our galaxy.

Image: Dust clouds in the foreground block the light from stars further away.

Credit: NOIRLab

Imaging the Milky Way in detail is extremely difficult. When we look at the milky way with the unaided eye, the light from its countless stars all blurs together, giving it its namesake milky appearance. The same problem happens when you zoom in, as there are so many stars that the light from separate objects can bleed into the same image, making stars appear different brightness than they really are.

Additionally, the resolution of a telescope is only so precise, and it can be very difficult to separate individual stars. Is it two dim stars or a single bright one? Moreover, the deeper you look the more robust the information you can get out of your data, but the deepest, most distant stars appear extremely faint. They are so dim that random noise like the flickering of Earth’s atmosphere or the electronics of the telescope can compete with the signal of starlight, a problem that can be partially solved with multiple exposures of the same region of sky.

Image: Telescopic footprint of the survey, showing which parts of the sky were imaged how many times (number of epochs) for a total of 21400 individual exposures.

Credit: Image adapted from Andrew K. Saydjari et al 2023 ApJS 264 28

Astronomers can also try to correct for noise by digitally inserting false stars into the image to see if anything looks suspiciously similar. If so, it might be an artefact.

These complications are without mentioning the dark dust clouds that permeate the Milky Way, making observations in just optical wavelengths difficult. This problem is addressed and partially mitigated by also observing in near infra-red light (the NOIR in NOIRLab) which can pass through dust clouds more easily than visible.

Image: The Victor M Blanco 4m telescope that performed the survey

Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/D. Munizaga

Together with the Pan-STARRS 1 surveys, which covered much of the northern sky, the combined images and datasets give a complete 360-degree panorama of the Milky Way in tremendous detail.

The perfect antidote for whenever you feel special.

Another falcon heavy launched carrying a classified payload for the USSF to geostationary orbit.

The National Science Foundation and SpaceX reach an agreement to mitigate the impact of Starlink satellites on astronomy.

Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne rocket failed a launch attempt, losing nine satellites.

ABL Space Systems RS1 rocket had a failed launch attempt.

SpaceX successfully completed a wet dress rehearsal of Starship, a critical test in preparation for a possible launch in May.

Upon clicking the "Book Now" or "Buy Gift Card" buttons a new window will open prompting contact information and payment details.