May 2025

The Sky Tonight - May 2025

May continues the season of Djeran – the season where the cooler weather begins. Maybe it will get here eventually? …

ExploreThe latest sunrise occurs in early July, as the Earth reaches aphelion on July 5th. Sunrise times will start to get earlier after this date. The Earth’s orbit is slightly elliptical, as all orbits are to some degree, and aphelion is the point when it is furthest away from the Sun in its orbit. The closest point, perihelion, is in early January.

The second eclipse season for the year occurs in early July, starting with a total solar eclipse over the South Pacific Ocean. Only the most intrepid will make it to a small coral atoll north of Pitcairn Island to witness it at its maximum, the majority of eclipse chasers will be in South America near the end of the path of totality. The partial lunar eclipse that pairs with the solar eclipse is visible to Australia, and the west coast will get to see the Moon setting into the Indian Ocean as it leaves the penumbral shadow. Maximum eclipse is at 5.31 am for Western Australia, when near two-thirds of the Moon will be immersed in the umbra, the full shadow of the Earth. More information at Eclipsewise.com or at timeanddate.com.

The map on the left shows the path of the total solar eclipse over the South Pacific on the 2nd July, then two weeks later there is a partial lunar eclipse centred over the Middle East that Australia will see most of – the Moon will set during the final stages for the west coast of WA.

Slender crescent Moon next to Mars, evening twilight

July 4

Earth at aphelion, its furthest point in its orbit from the Sun

July 5

Moon above Jupiter, evening sky

July 13

Moon below Saturn, evening sky

July 16

Slender crescent Moon to the left of Mercury, morning twilight

July 31

Mercury bookends July with an appearance in the evening sky at the start of the month before swapping over the morning sky for the end of the month. Mars will be nearby, in the evening twilight, but the two planets may be hard to identify as they will be around seven degrees apart – that’s about the width of hand if you hold your arm outstretched in front of you. A new crescent Moon will be next to Mars on the 4th, and Mars and Mercury will set together on the 9th.

On the opposite side of the sky a more relaxed show is going on. Jupiter is still shining brightly under Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius the Scorpion. A little further down is Saturn, which reaches opposition this month on the 10th. This means it is opposite the Sun as seen from Earth, so it’s at its brightest and best for the year. The Moon will be just below it on the 16th.

Venus has now moved too close to the Sun to be seen in the morning sky. It will be out of view now for around four months. We will next get a view of it in October, when it returns to the evening sky for summer. But wait! Remember I mentioned Mercury at the beginning of this section? It moves up into the morning twilight in the last few days of July. A thin crescent of the old Moon will be to the lower left of Mercury in the dawn sky on the last day of the month for those with sharp eyes and low north-eastern horizons.

Saturn and the Moon on the evening of the 16th July 2019.

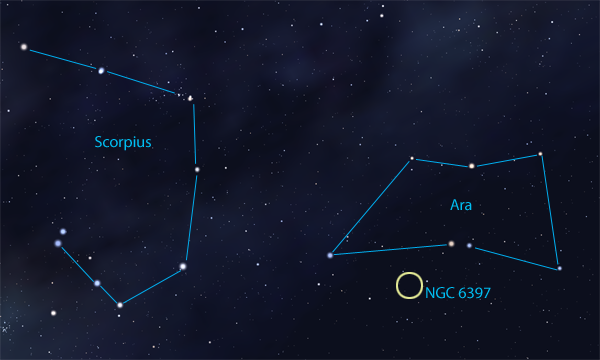

Scorpius is one of the most recognisable constellations in the sky – he actually looks like what he’s supposed to look like. He has three (or four) stars that mark his head, which run at right angles to his long curving back. His tail starts with a sharp bend and curls around like a fishhook. You could almost imagine he’s got it hooked in the star clouds of the Milky Way and is pulling them along behind him in the sky.

Back near the head is the giant red star Antares, which means the Rival of Mars. When the star and red planet are together they do look similar in colour and size. This star is nearing the end of its life, as it has swelled up to 300 times larger than our sun is now, but it still has some way to go before it finally makes it exit from the stellar stage.

Scorpius is said to be in the sky because of Orion the Hunter. Orion was the best hunter in the world, the story goes, and he was quite boastful and vain about this. He boasted he could catch and kill any animal in the world! The gods did not like to hear this, so they sent a creature that would teach Orion a lesson. The scorpion snuck up to Orion and stung him on the foot, and as Orion writhed in agony from the poisonous sting he crushed the scorpion, so that both died. They were put in the sky among the stars but on opposite sides of the sky, so that Orion sinks in the west Scorpius comes up in the east, and they can never fight each other again.

Jupiter is under Antares in July 2019.

Globular clusters are large clusters of hundreds of thousands of stars that are probably left over bits from when the galaxies formed. Most of the stars in the cluster are very old. Because the clusters typically orbit around the outside of the galaxy they retain a round, globular shape, which is how they got their name. We can see around 120 globular clusters that belong to our galaxy from Earth, and we can see thousands around other large galaxies beyond. At this time of year when the centre of the galaxy is overhead in the evening sky, we have the opportunity to observe a large number of our local globulars as they are concentrated around the middle of our galaxy.

NGC 6397 is a bright globular cluster in the constellation of Ara the Altar. It is not far from the curved tail of Scorpius and is bright enough that you may even see it with the unaided eye in a dark sky. Binoculars will pick this object up with little trouble – but be careful, there are number of other globulars in the area. NGC 6397 should be the biggest and brightest one there. It lies only 10,500 light years away, making it one of the closer globulars to us, and that’s why it appears so big and bright in the sky.

The Eagle had landed, and Neil Armstrong was about to step onto the Moon. Would he sink into a deep layer of dust, or would he find a solid surface? This was actually a debate that was going on at the time of the first Moon landing, and it was quickly shown that the surface was only covered in a thin layer of dust and was quite firm underneath. “One small step for man, one giant leap for Mankind.”

Perhaps you know someone who was alive on that day man first walked on the Moon. What story do they have to tell of that day? Millions of people around the world watched it live on television, with schools in Australia making special arrangements for their students to watch as it happened in the middle of the day here.

There were six successful landings, and the abandoned mission Apollo 13 that had to return without attempting to land. Most of those missions left special reflecting panels behind that we can still bounce laser beams off today. These help us measure the distance to the Moon, and its position, as it slowly moves away from us at about 4cm a year.

The retroreflector left on the Moon’s surface by Apollo 14. Laser beams are bounced off this reflector and their return journey timed to measure how fast the Moon is moving away from Earth. Image credit

When I’m doing outreach, people often ask why don’t we swing the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) around to image the sites and get proof of the landings? There are several good reasons for this, firstly because the Moon is so bright, and would drown out the delicate sensors inside the telescope, but secondly because the HST is not big enough. Ah, what? Yep. The main mirror on the HST is only 2.4 metres across, which means the smallest feature it could see on the Moon would be 40m across. Any of the landing sites would be contained within a pixel on an image.

So how do you solve that problem? You send a space probe to circle the Moon more closely and make it capable of imaging the surface down to a resolution of 50cm. That is what the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has been doing the last 10 years. It has built up a library of images of all the Apollo landing sites and you can look through them all here: lroc.sese.asu.edu/featured_sites#ApolloLandingSites

Explore a bit more while you’re there. There is more to see than you might expect.

Image comparison of video from Apollo 17 as it left the surface of the Moon and 39 years later when the LRO imaged it from orbit. You can see the same tracks and disturbed ground. Image credit

Upon clicking the "Book Now" or "Buy Gift Card" buttons a new window will open prompting contact information and payment details.